Qui Nhon’s Camp Keystone

Recently I was surfing the net when I came across a paper written by college student Aaron Willmore about his grandfather’s time with the 93rd Military Police Battalion in Qui Nhon, Vietnam. (https://www.scribd.com/doc/249046798/grandpaprofile1).

I had been searching for information about Camp Keystone, Qui Nhon, 1970/1971. It seemed to have disappeared from history and now, thanks to Aaron and his grandfather, Thomas L Wilson, I understand why.

Tom was assigned as a clerk with HHD, 93rd MP Battalion at Camp Granite in Qui Nhon, but when the drawdown of U. S. troops began, Camp Granite was turned over to the ARVN (Army Republic of Vietnam). As part of our reduction in force and consolidation, Tom and HHD, 93rd MP Bn moved to Camp Keystone in early July 1970. The 93rd’s stay at Camp Keystone didn’t last long. The battalion moved to Qui Nhon’s Quincy Compound in May 1971.

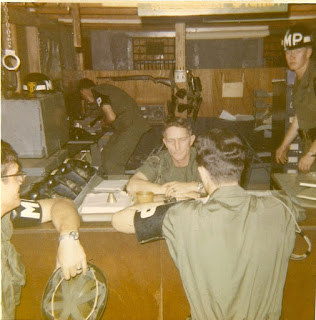

SP4 (Acting Jack) Wilson left Vietnam in April 1971. My tour of duty in Vietnam was from October 1970 until my DEROS in July 1971. I was initially assigned to the 127th MP Company, which was located on the back side of Qui Nhon airfield. In January 1971, I moved to HHD, 93rd MP Bn at Camp Keystone, where I initially served as the S-1 and later in the S-2/S-3 shop. As such, Tom and I served together from January 1971 until his departure that April.

The Qui Nhon Provost Marshal’s Office was located on Camp Keystone at that time and, while I performed staff functions during the day, in the evenings I would pull Duty Officer out of the Qui Nhon PMO once or twice a week. Tom would work in the S-4 shop during the day and every once in a while he would be the Duty Officer’s driver at night. In any event, the battalion’s stay on Camp Keystone lasted only about eleven months, albeit the reason it was difficult to find any historical record.

I called Tom, who is now an attorney, and chatted with him about his grandson’s paper. I had always assumed that the Keystone name was derived from our battalion crest, which had two keys crisscrossed over a stone column; but Tom suggested it had more to do with our MPs being dubbed the Keystone Cops.

In reality, the name had more to do with Operation Keystone which encompassed the reduction in force and withdrawal of U. S. forces as part of the Vietnamization program. Initially, under Operation Keystone Eagle, which began in June 1969, forces within the Qui Nhon Support Command area were redeployed without affecting the overall structure of forces. It basically involved space reduction. Later, as Operation Keystone continued, forces were withdrawn from Vietnam and redeployed stateside.

Another contributing factor was probably the fact that Binh Dinh Province, to include Qui Nhon, was considered to be the keystone of South Vietnam’s central provinces. It was the political and economic hub of South Vietnam – the richest and most populated.

Aaron’s paper also made mention of the fact that Camp Keystone had previously been a coast guard station. I had forgotten that and was pleased that he made note of that historical tidbit.

Although the 93rd’s tenure at Camp Keystone was relatively short, it was not an uneventful period. Qui Nhon suffered two severe civil disturbances/riots in December 1970 and February 1971. The Ammunition Supply Depot experienced three attacks, resulting in major explosions felt all over the city – one on January 7th, another on February 20th and yet another on April 28th. In addition, just as the February riot was beginning to abate, the International Shell Storage Yard was attacked the evening of the 15th, resulting in a massive fire, which our MPs fought well into the next morning. Explosions from that could be heard all over Qui Nhon. One of our MPs was blown off the seawall on the water side of the storage yard. Fortunately the water, although filthy, was shallow and he was pulled out safely.

I had a recollection of the Vietnamese protesters tear gassing our compound during the December riot and remembered being without a gas mask because I was in the process of transferring over from the 127th Military Police Company. The S-1 shop filled up with CS as I stumbled around trying to use water to clear my eyes. My phone conversation with Tom revealed that what really happened was that one of our guys initiated the CS and one of the rioters just threw it back over the fence line.

Camp Keystone may have been the home base of the 93rd MP Bn for only eleven months, but it certainly was an exciting, action packed time for our Keystone Cops and their support personnel.

Thanks to Aaron’s paper about his grandfather, Thomas L Wilson, that history will be preserved.